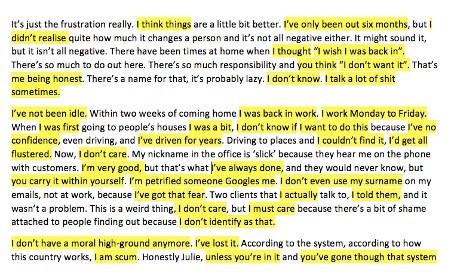

i-poems are created from the ‘I’, ‘we’ and ‘you’ statements as they appear in the narrative flow of the interview transcripts. They become powerful and personal statements of intent that prioritise the voice of the narrator.

About iPoems

This method belongs to a social constructionist, epistemological position that recognises that human experience is bound up within larger relational dynamics. It centres on the ‘voice’ of the respondent and is associated with a ‘feminist interpretative lens’, one in which the ‘self is viewed as having multiple selves or voices, in contrast and conflict with one another’.[1]

1. J.M. Parsons (2017), “‘I Much Prefer to Feed Other People than to Feed Myself’: The ‘I-Poem’ as a Tool for Highlighting Ambivalence and Dissonance within Auto/Biographical Accounts of Everyday Foodways,” The Journal of Psychosocial Studies 10(2), available online.

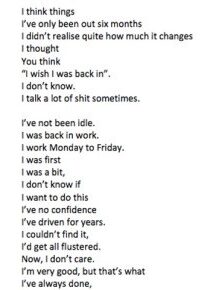

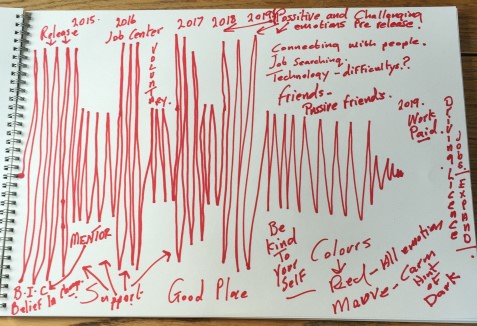

The power of the i-poem, as I have noted previously, is intensified when it is spoken/listened to, particularly if it is the voice of the original speaker. It is with this in mind that I gave the i-poems to some of the men, who then read them aloud whilst being audio recorded. These audio files have since been used alongside their timelines and photographs to produce short film clips. Indeed, in an attempt to give voice to one of the most vilified and marginalised social groups, the research has become a process of making and unmaking, organising and arranging a kind of temporal bricolage that reveals alternative rehabilitative conceptualisations of wellbeing and meaning beyond the notion of released subjects as risky and potentially transgressive. Instead, there is vulnerability and resilience.

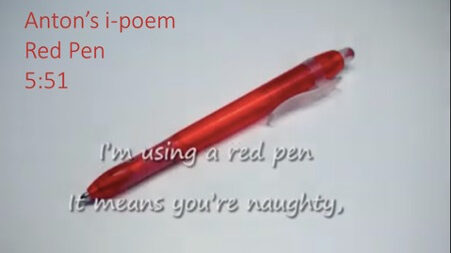

To date there are three films ready to view, with others in production. The process of creating the films is a collaborative effort. Not only with those participating in the research itself, but others as well. Notably significant input from Rob Giles, a University of Plymouth IT specialist and videographer, who interpreted the i-poems in order to create ‘Red Pen’ and ‘Dreaming of Fishing’. And Daniela Chivers, a stage 2 sociology student on a volunteer placement at the resettlement scheme, who worked with Rob on ‘Quentin’s i-poem’. They both engaged in work with the written and audio files of the i-poems, as well as the photographs contributed by the men

Producing iPoem Films

The films were sent to the men for them to comment on and for them to suggest changes. The films have since been shown to members of the resettlement team who worked with the men previously and at a number of conferences this year (2020)[2].

2. 4th European Congress of Qualitative Inquiry, 5th -7th February 2020, University of Malta. See: Parsons, J.M. (2020) Finishing Time, ‘I-Poems,’ and the ‘Pains of Release’ into the Community After Punishment , ISRF Bulletin

Collaboration

This collaboration has resulted in three short films ready to view, with others in production. The process of creating the films is a collaborative effort. Not only with those participating in the research itself, but others as well. Notably significant input from Rob Giles, University of Plymouth IT specialist and videographer, who interpreted the i-poems in order to create ‘Red Pen’ and ‘Dreaming of Fishing’. And Daniela Chivers, a stage 2 Sociology student on a volunteer placement at LandWorks, who worked with Rob on ‘Quentin’s i-poem’. They both engaged in work with the written and audio files of the i-poems, as well as the photographs contributed by the men. The films were sent to the men for them to comment on and for them to suggest changes, for example Quentin requested the removal of an image at the end of his film.

Opening stills from the films:

Rob’s Commentary – connecting with the listener

When I was first presented with the idea of the i-poem I found it intriguing. As a lyricist and songwriter, I have explored automatic writing in order to achieve an unconscious flow of spontaneity. Abstract lyrics are vehicles for lyricists to enable a listener to formulate their own meanings and interpretations creating in turn a personal connection for the listener with the music. The process of creating an abstract lyric, however, is likely to be less random than the writer imagines. Rather like a dream there is often a profound sense of emotion and state of mind flowing from the seemingly random words and sentences. The result is often a deeper insight into the conscious state through the subconscious window. These conclusions are simply reflections of the process I have engaged with and something I can certainly reflect on as having a relevance when revisited.

Emotional narratives

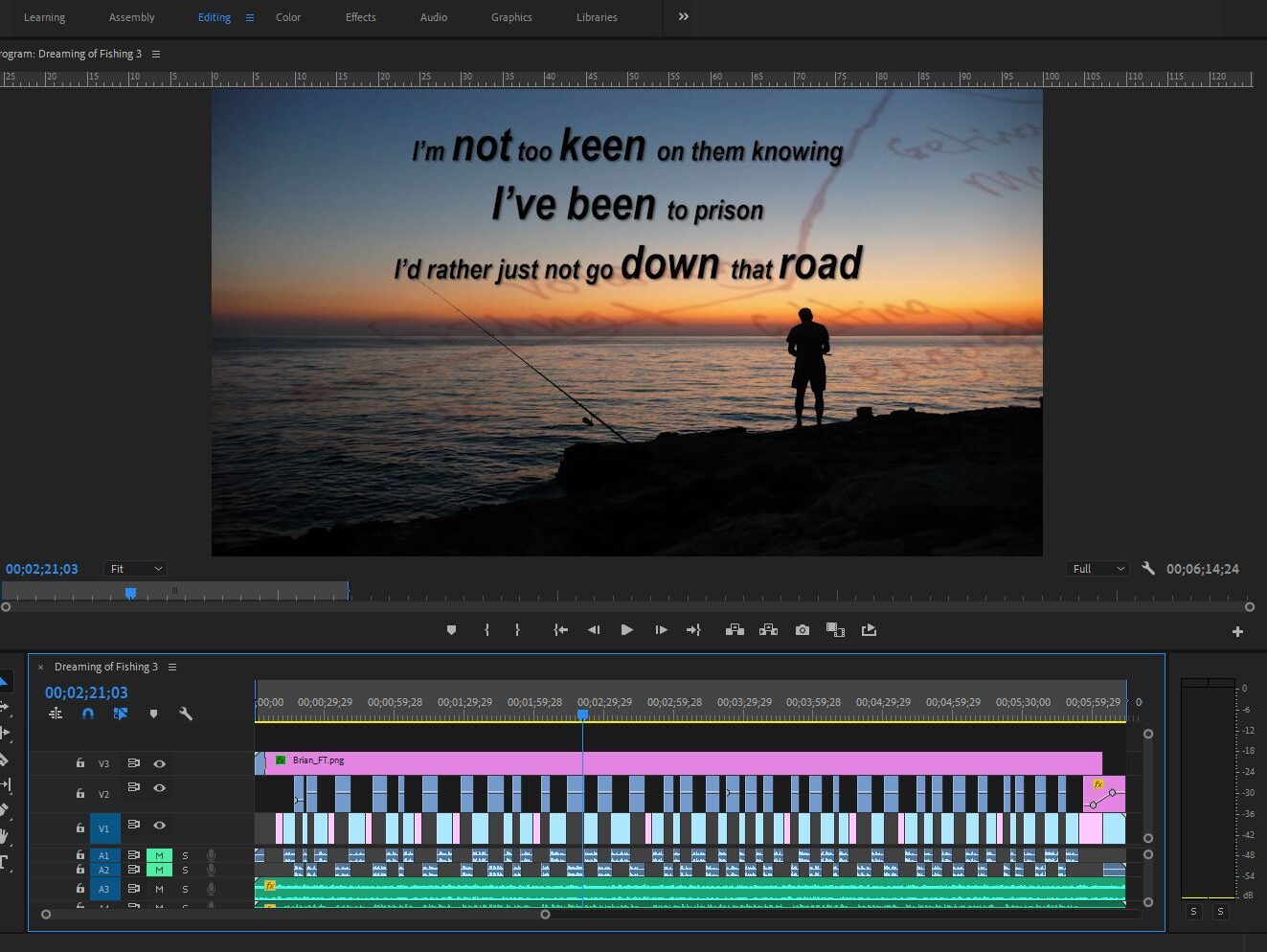

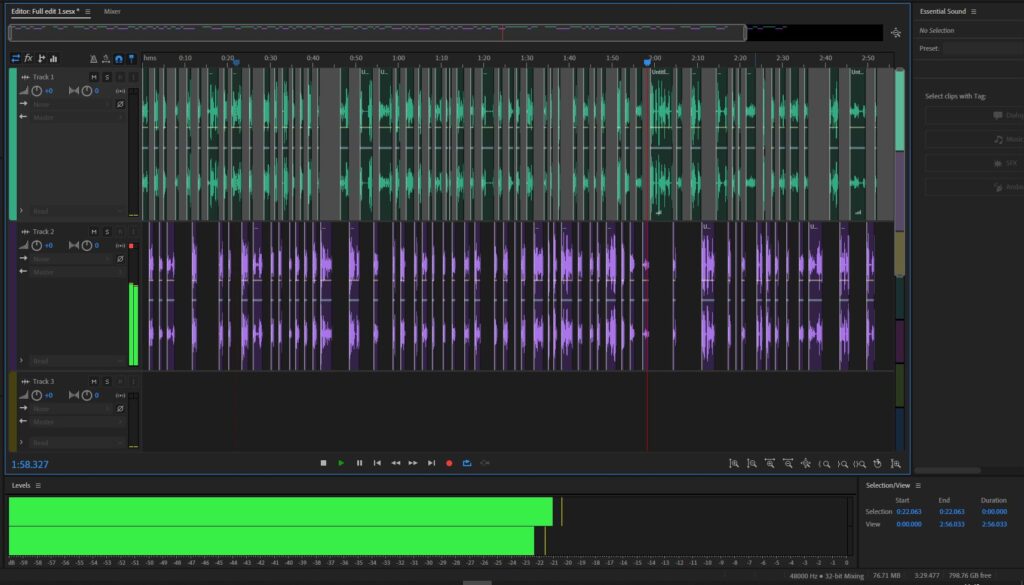

The i-poem although more targeted seems to offer another way to reveal a subconscious emotional narrative almost as a subtext that can be explored. The i-poems I received were constructed from interview recordings that had been transcribed into the verses that were then given back to the interviewee to be reread with the recording made. The original concept was that this recording together with personal pictures from the interviewee and their timeline could be combined to form a video. This process was slightly extended upon for the first production entitled ‘Red Pen’. The immediate issue encountered was a lack of pictures with the necessary resolution to be used however we had a deadline so together with some additional images and some transition effects an interesting result was created with some carefully chosen mood music. Two versions were made, with and without text. We agreed that the version without the text was more successful highlighting the voice, however this i-poem was to be presented at an exhibition where the sound might be difficult to listen to.

Photographs for an i-poem can present privacy issues or do not suitably reflect the subtext. To address this I decided to focus more specifically on the poetry itself for the i-poem entitled ‘Dreaming of Fishing’. Using a sequenced delivery to animate the text over a single image, this short film helped focus the meaning further and again enhanced the voice narration. The continuous adaption and progression of the process is set to continue with each new film building on the last to further enhance and develop this series.

Daniela’s comments

I was involved in putting together an i-poem. I was given a range of pictures that I put in order that matched with the voice recording. I had help in putting the video together, so it all played smoothly. We decided not to put the words over the top of the pictures because the recording was clear enough to hear each word. Furthermore, we didn’t want the words to cover up the pictures as they were key to what the trainee was saying and need to be clearly seen. I added subtitles to the video, so this can be turned on if needed. Whilst volunteering at Landworks, I was able to take my own pictures. I feel that this worked well because I had listened to the transcript and then could take my own pictures to go with what was being said. I didn’t want to use all my own photos when putting together the i-poem as some of the photos chosen were from the trainee and I wanted to keep it personal to them.

What is striking about the i-poem films is that the focus on the ‘I’, ‘we’ and ‘you’ statements distils the overall narratives from the men, with interviews lasting from one to two hours concentrated into four to seven minutes. These become powerful statements about the ‘pains of release’, notably in terms of the enduring impact of criminalisation on the sense of self. When listening to and watching the films, key themes emerge from each of the men. In Anton’s story, he uses a ‘red pen’ to draw his timeline as it symbolises being naughty. He says:

I would never turn my back on my old self

Extract from Anton’s iPoem ‘Red Pen’

I also think about my old self every day.

I don’t punish myself these days.

I have done in the past.

I’ve still got regrets,

I’m accepting it

I see someone

I don’t say

I gravitate

I can’t have them as friends

[…]

In Bryan’s interview, he sends me photographs of his new wife and the fish he has managed to catch night fishing. He says:

I’m not in touch with my old friends

Extract from Bryan’s iPoem ‘Dreaming of Fishing’

One of them,

I am

I realised

I haven’t really got that much in common

I didn’t want to be living like

I was before

I went in prison

One of them I still hang around with

I go fishing

I’ve got new friends

I sort of muscled in

I don’t know whether it’s just getting older

I just prefer to go off with Janine or just be on my own

During Quentin’s interview, he sends photographs and shows me the pottery he has been making in his garage at home. He says:

you’ve been in there for two years and

Extract from Quentin’s iPoem

you’ve lived your life a certain way,

you come home,

you’ve got all this freedom and

you don’t go out the house.

I still don’t.

I’ve not had one friend come to see me

I haven’t got any friends,

I’m ok with that.

I got home,

I was sat on the front there,

you could see him talking

I was just looking at his mouth moving,

I had this little bubble in my head

“why are you talking to me?”

For all of the men there are difficulties in forging new relationships, as well as re-establishing or maintaining old ones as a consequence of criminalisation. They all engage in various strategies, from spending time alone, to night fishing and spinning pots. However, their accounts are also powerful reminders that social reform is needed for criminalised individuals to be fully reintegrated into the community after punishment. As criminologist Fergus McNeill reminds us, the problem of desistance is social as well as individual; acceptance of a former prisoner is a community matter and not just a private business [3].

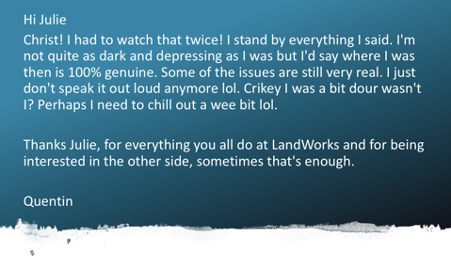

Sometimes, though, as Quentin comments in response to seeing his film a few months after his interview:

Thanks Julie, for everything you all do at the Resettlement Scheme and for being interested in the other side, sometimes that’s enough.

Quentin

References:

3. F. McNeill (2012), “Four Forms of ‘Offender’ Resettlement: Towards an Interdisciplinary Perspective,” Legal and Criminological Psychology 17(1): 18–36.